Alternative Ammo: .243 Winchester vs. 6mm Creedmoor

I’ll be upfront .243 Winchester is by far the most “alternative” ammo choice I’ve tried in this series to date. My personal editor to blame and he’s not letting me down this ammo 6.5 Creedmoor like I’ve been trying to (Editor’s Note If I permitted the 6.5 Creedmoor, he’d write nothing but it was the 6.5 Creedmoor),so I chose the most suitable alternative. The 6mm version of Creedmoor cartridges happens to be the most to be popular in the line and, just like its more popular counterpart however, it’s not what it’s portrayed to be due to several factors. This article will concentrate not solely on a particular cartridge (the “alternative” which is usually is the case with this particular series) being superior however, it will focus more about the reality that a newer cartridge does not necessarily mean superior by default.

For those who handload there has never been any big fan of any of the hyped “wonder” cartridges. Why? because they’re not very impressive. They’re not inferior cartridges, but that — as this series was created to prove, if you load the cartridge manually one of them “super” cartridges could be beat, if not even beat, by less popular or popular cartridges.

When I look at the issue from a hunting angle my main objective is to obtain the highest ballistics that will kill an animal in a humane and ethical manner and with the least amount of effort. But, these more modern cartridges aren’t doing anything I’ve never done before using a different cartridge; there’s no significant benefit from any of these modern cartridges. In addition the cartridges have resulted in a problem: shooters frequently believe that they’re better shot than they actually are because they believe in the cart’s hype, but they actually need practice or to define what they believe to be an the acceptable distance. Marketing can cause a false sense of confidence among hunters because of a rumored feature or characteristic, yet hunters are still plagued by the same problem, and it’s been a problem for them.

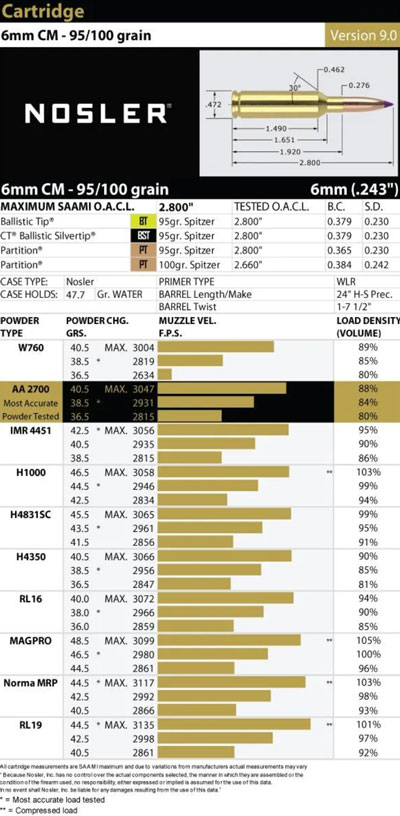

But I digress. Let’s examine six millimeter Creedmoor and then compare it with it with the .243 Winchester for a tidy illustration. In terms of ballistics, both are basically the same in that they go toe-to-toe when involves reloading data that is in accordance with velocities and grain weights. In some situations the 6mm Creedmoor wins while in other instances, there are instances where the .243 will prevail. Each of the cartridges is fired with a shorter action, which means that the rifle weights and accuracy derived from the action’s rigidity is irrelevant, and neither are the advantage of a longer barrel, since the capacity is similar across all cartridges as well. Therefore when two rifles are identical, one is in .243 Win. while the second is Creedmoor 6mm–neither cartridge will be recognized based just based on the characteristics of the rifle.

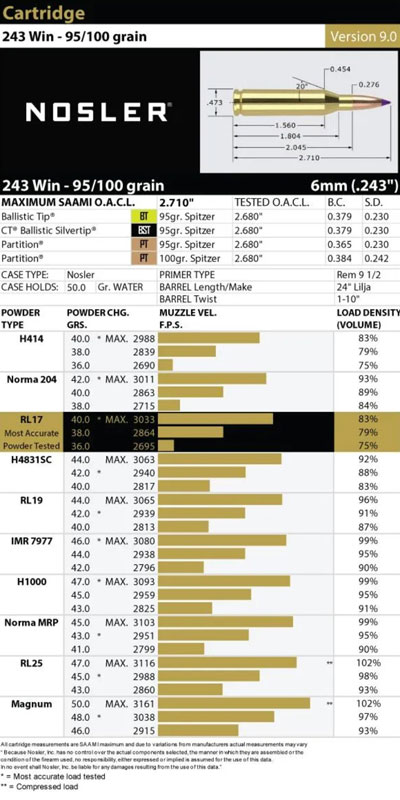

“But what’s the twist rate? ?!?! It is possible to shoot larger bullets due to the twist rate but aren’t able to shoot from that .243,” say Creedmoor Harpies. But what do you think? I could get a 1:8 twist barrel mounted on my .243 If I wanted to and then shoot heavier bullets, too (mostly match bullets, not intended for hunting in the first place). “What is the issue with the length of the bullet? You can’t place long bullets in a proper way due to the smaller neck of .243!” Again, the majority of match bullets that are not designed for hunting would not perform effectively in .243 Win. Yes however, it’s neck on the 6-millimeter Creedmoor is just .03 of an inch more at the base, as illustrated through the Nosler’s drawings of every cartridge. It is true that .03 or an inch is an enormous difference in the way that bullets are seated due to the Ogive of the bullet (the curvature of the bullet that runs from the nose and ending at it’s body prior to it straightens) I’d say that you’re too focused on the ballistic coefficient or the profile. Hunters should be looking at the performance of the bullet’s final stage. A bullet could be the most aerodynamic and efficient bullet around, and do absolutely nothing when hunting game. The majority of high BC bullets are designed to make holes into paper, not organs that are vital and the ethical places where hunting is conducted most of the time do not need bullets that fall with a minimum of an MOA at 400 yards.

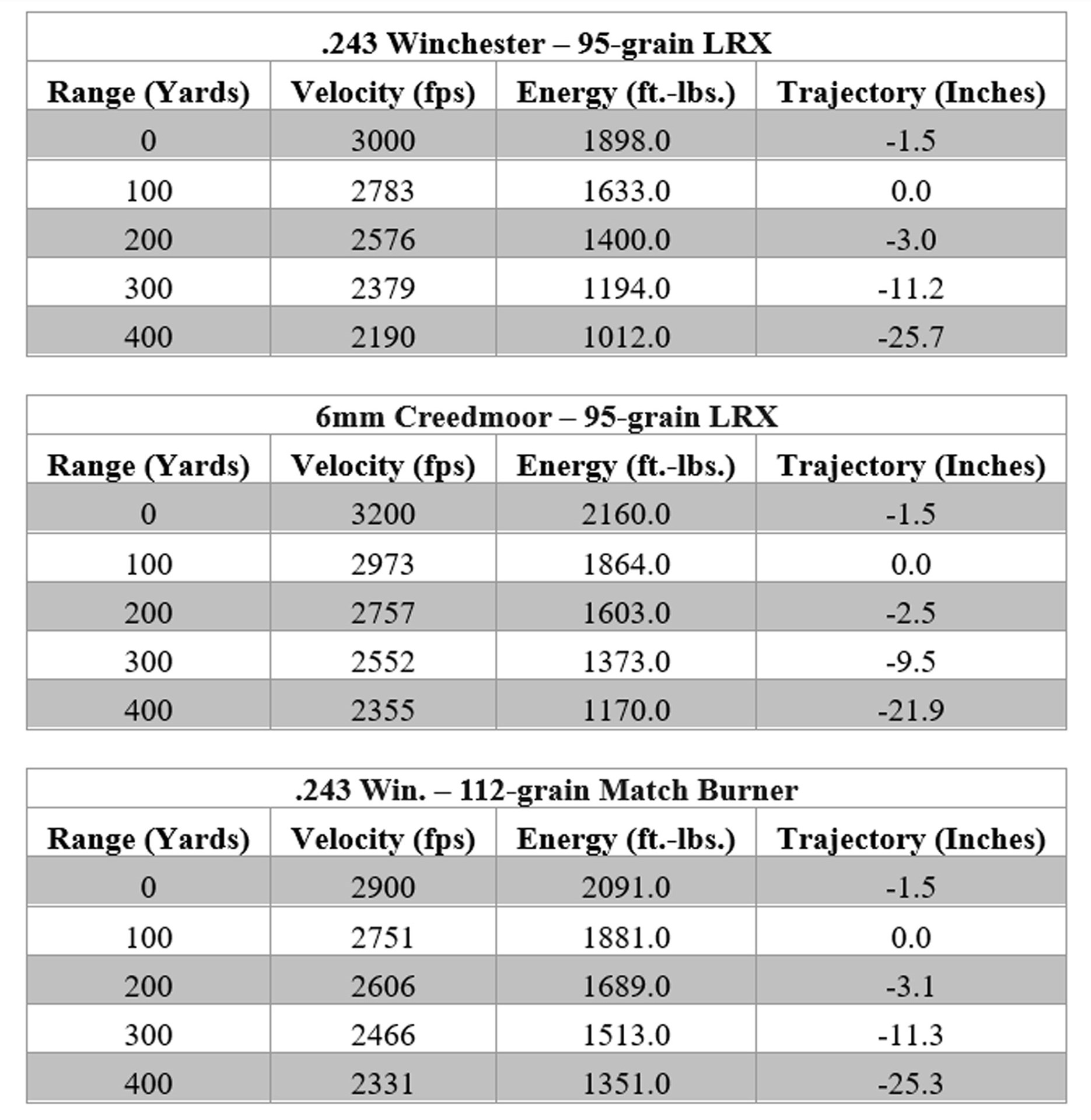

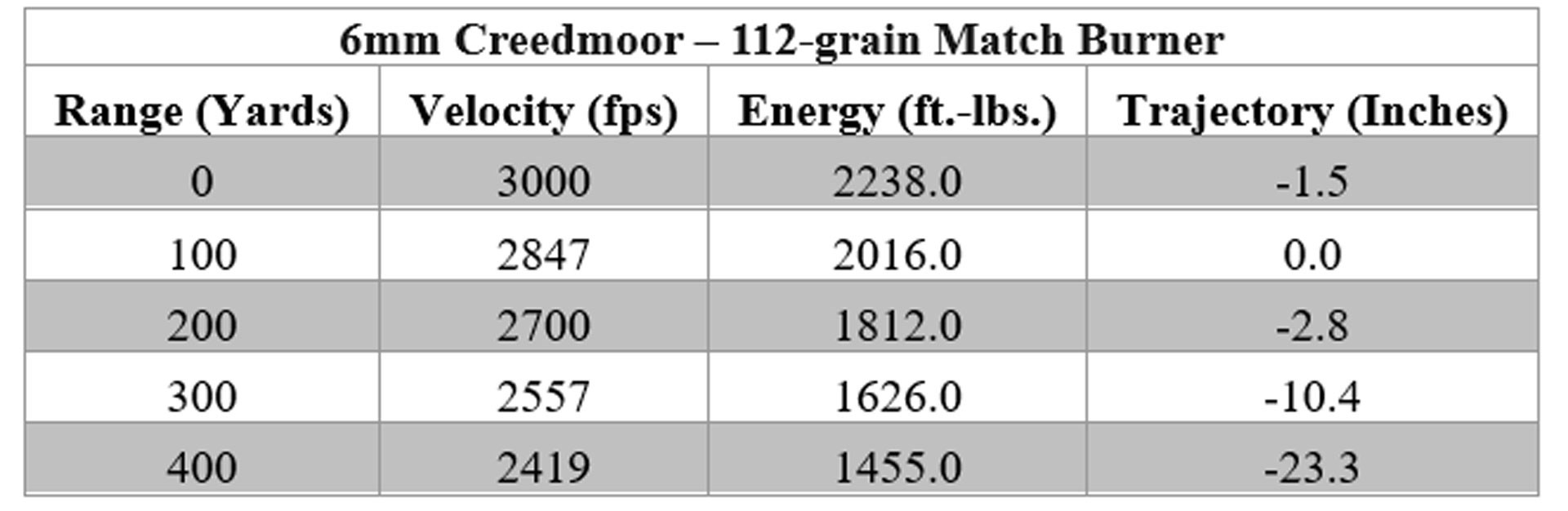

To illustrate this, you can use for example a Barnes 95-grain LRX as well as the Barnes 112-grain Match-Burner. Each bullet’s length will be 1.270 inches or 1.331 inches and 1.331 inches, respectively. Barnes load data — which indicates both bullets firing in each cartridge, which means even long bullets could be shot with the older .243 Win.–gives about the same velocity for a variety similar powders in the cartridges. Look at below for a table (results of Hornady’s Ballistics Calculator):

The tables indicate that there’s at least an inch of fall between the cartridges. This means that when a shooter doesn’t manage to keep an MOA-sized group at this distance drop difference is not important since the size of the group will be greater than the drop variance regardless.

As someone who worked working in marketing roles prior to that, I can attest to some buzzwords and terms that are “inherently” connected to anything that involves accuracy. “Inherent” is, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary means “belonging to or being aspect of an individual or thing.” If something is “inherently precise” it simply means that the item is greater than likely to be accurate, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s more precise by default. In the case of Creedmoor (pun intended) it’s because there’s something in the cartridge that makes it better suited to being precise when compared to other ammunitions available, but it does not mean that it is. That’s the reason you don’t have a an assurance of money back for the 6-millimeter Creedmoor gun or ammo. The possibility of this changing is based on the capabilities of the shooter more than anything else. Any issue with the form of the shooter such as the trigger squeeze, flinching, breathing or breathing. This means that all that potential accuracy – assuming that the shooter has an excellent rifle and ammo that’s reliable in real-world settings–will go out of the of the window.

It’s not to suggest that it’s accurate (see my last article on how the .375 Ruger VS the .375 H&H, and the reason cartridges with belts can be “inherently” less precise) however, by manually loading myself with my personal .243 Win. ammo, I’m able to often outdo the accuracy of a 6mm Creedmoor cartridge’s “inherent” accuracy. What can I say? Since I’ve tried it; my handloads came out of the Ruger M77 MKII in .243 Win. A 100-grain bullet can reach almost 3,100 fps. I also created a 3-round group inside the form of a two-inch circle at 500 yards, which is superior to the MOA that is the usual accuracy normal. In the past, I’ve put in an enormous amount of effort into this rifle to get this kind of precision from the firearm. I’ve altered the stock to ensure that the barrel was free-floated. I also installed a top-quality optic and added an overhaul of the trigger. It’s far less expensive than buying a brand new rifle with the expectation of something excellent or even better. It’s a problem of diminishing returns.

What’s the point with all this? This raises the question of at what point does the concept that there is “inherent” accuracy is no longer worth the cost? The fact that a new cartridge is likely to be more precise because of its design doesn’t mean that it will make any person more proficient at shooting. There are a myriad of factors that affect accuracy that it’s a pity to throw away an extremely accurate firearm, especially one that has an astonishingly precise handload designed for it, just because it doesn’t have an advanced, “high-tech” design change like a shoulder angle, or an extended neck. It is not a problem until you reload the ammo. Those changes don’t affect the ammunition that you purchase since you aren’t able to alter the bullet’s depth until you reload. You’re restricted to the ammunition that the manufacturer provides you with. If you do decide to refill, the neck’s length can be compensated for through other ways. Are they beneficial? Sure. Need to be accurate? In no way.

Need more proof? Take a look at the accuracy tests from the old rifles that muzzle load. What is the significance of this? The rifles mentioned don’t have cases If “inherent accuracy” based on the case is true muzzleloaders must have extremely poor accuracy when compared. One example is that an editor from American Rifleman tested an American Rifleman Model 1841 Mississippi long rifle using iron sights from a sitting position and printed a two-inch group in 100 yards. Apparently, that’s horrible. Reports of long-range events using Whitworth rifles show muzzle-loading guns shooting over 1,000 yards and with sub-MOA accuracy. For those who are interested in reading Dark Web Canada Here are two additional excellent examples. The creator of CVA Paramount Hardware was able to create three-shot 100-yard groups for less than a half-inch (.62″) as well as the average group forming .75-inch groups and the biggest group with just a little over 1 inches (.82″) that means that the projectiles are likely to be touching, given that the size of the group is much smaller than the diameter of the bullet (in this instance, .40 caliber). Traditions NitroFire Traditions NitroFire also shot a few smaller groups–with a bullet with a greater diameter (.50-caliber) in addition to two different ammunitions that measured .375 inches when you are at 100 yards with the other weighing in at .5 millimeters at 100 yards. It’s terribleaccuracy I’m sure. If only muzzleloaders could shoot more accurately …

Take a look at even the most dull tool for cutting A loose screw that’s not properly torqued or a barrel not free-floated fully. It doesn’t matter what, there may be a multitude of reasons rifles aren’t precise, but none is directly related to the cartridge.

Do you think that a case’s shoulders neck length and angle are important? If a muzzleloader is the simplest you can find out of a musket that isn’t rifled and does not have the latest accuracy enhancements made by a cartridge in any way, can produce these types of groupings at 100 yards be assured that your Creedmoor’s 6mm neck length and shoulder angle will not improve your performance the extent you’d like particularly when compared to the traditional .243 Win. You can extrapolate these results to the chest of a deer or neck, and I’d say that the case is that unless you hunt at more than 1,000 yards, the older cartridge, which is less popular, will work well.